Reality is Complex & Messy -But We Could Focus on What is Good Instead of What is "True"

[This post is an essay version of a Twitter thread of mine, which can be found here.]

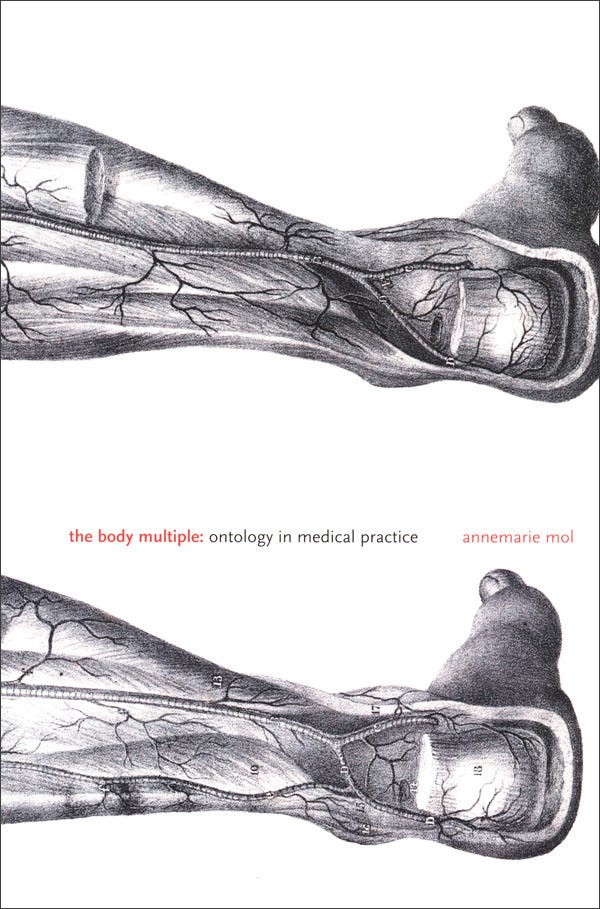

Among the books on healthcare I have found most helpful is “The Body Multiple” by Annemarie Mol. It primarily discusses how hospital medicine works despite its inherent messiness. The complexity and messiness of a hospital system, with layers upon layers of different departments and doctors and medical teams and laboratories etc., is well-known. In the book, Mol provided an excellent analysis of how, despite its complex nature, the hospital overall works. She researched at a Dutch hospital in the 1970s and 1980s, and the book was published in 2002.

Here’s a video in which Mol talks about this book — 20 years after it was published:

In the book we learn how, in a large hospital, different departments & practitioners interpret the same ailment (atherosclerosis) in different ways. There r always tensions & conflicts between teams & practitioners, but by & large the hospital continues to function & to provide good care.

“If atherosclerosis is a thick vessel wall here (under the microscope), it is pain when walking there (in the consulting room), and an important cause of death in the Dutch population yet a little further along (in the computers of the department of epidemiology). Reality is varied.”

Ever since I read the book many years back, I have often found Mol’s insights helpful in thinking not just about medical care, but also about the world outside the hospital — our societies & nations in general. There is messiness and “varied reality” all around us, after all. Eg, during discussions on something as workaday as which restaurant has the best food, to something as heavy as why did the partition of British India occur, we are often like: “Hmm, this is true” at one moment, & later, “Yeah, thats also right.” Reality is frequently varied.

A central challenge in human societies is hence not very different from a central challenge in medical practice: How to best deal with multiple interpretations of the same entity, and how best to deal with the uncertainties and doubts involved therein.

Think of the debates and heated conversations you have had with friends & others on some or the other complex aspect of history or politics. A common experience is that fixating on what ”really happened” or what was “really said” etc. often just leads to inconclusiveness and circular give-and-take. Mol’s answer to such challenges is: Often, it’s better & more productive to leave aside what (we think) we know, & focus on what we can do. Debates on what’s “true knowledge” will often be endless & circulatory: often, it’s better to redirect ourselves to what’s “good action”.

Of course there’s variety & multiplicity even in what are considered “good actions”, just as in medicine there are multiple ways of approaching the management of the same ailment and the same severity of an ailment. Here again, the hospital provides important insights:

“That there are alternatives to each particular practice does not turn the hospital into a state of permanent turmoil. Though nothing is certain, the permanent possibility of doubt does not lead to a permanent threat of chaos. Tensions crystallize out into patterns of coexistence.”

This is a hugely relevant insight for broader social issues. One example is the unfairly strident critiques that many people level against democracy as a system of politics and governance. These criticisms frequently expect democracy to conjure stuff that it does not even promise! It is actually much more helpful to see democracy as a system which will help us not eliminate tensions, but “crystallize [tensions] into patterns of coexistence.”

With respect to doing “good” in medical care, Mol writes that in her observation, the sets of actions which attempt to “rationalize” medical practice — through impersonal bureaucratic, technological, & statistical interventions — have made patients worse off:

“Rationalization starts from the idea that the problem with the quality of health care resides in the messiness of its practice. However, even if it may be messy, practice is something else as well: it is complex.”

Around 25 years ago, Mol argued that the clinical aspects of medicine (the raw, human, intimate, messy part of the patient-hospital interaction), will adversely suffer if subjected to too much streamlining and standardizing in the name of making medicine more “efficient”. She wanted policymakers to understand that the complexities of medical practice are not inherently bad and do not automatically need to be flattened out into uniformity.

One of the most significant takeaways of Mol’s book for me is that it shows how it’s really important to be comfortable with complexity, doubt, uncertainty, & messiness. In fact, being comfortable with complexity (of people and societies and cultures) is a hugely crucial social skill that needs to be learnt & taught widely in schools & colleges.

When we are comfortable with messiness, it helps us be receptive to the much more productive and reachable goal of “taming” tensions and conflicts, instead of the dangerous and always-elusive goal of “eliminating” tensions and conflicts.

This is in fact something which happens everyday in hospitals and clinics: there is far more of “managing” and “keeping under control” of ailments, rather than completely abolishing illness (which anyway is impractical and impossible). And just as Mol cautions us to be wary of those in healthcare who come with promises of “rationalizing” it, we also better beware of those in politics who approach us with grand promises of streamlining the complexities & messiness in our society to make it “great again.”