A Code of Gentoo Laws: The Origins of Modern “Personal Laws” in South Asia and India

[Note: This is a long essay, and through it I hope to present an example of a typical historical research article based on secondary sources. That is, the author writes on a particular topic by solely or mostly using existing articles, books and materials by other scholars, as opposed to researching “primary” historical sources. While the author might (or might not) make original novel arguments and present new perspectives, they [ought to] acknowledge and cite other scholars whose original research and ideas helped them arrive at those arguments. In fact, most books by “popular” history-writers belong to this genre, often called “historical synthesis”. Even though writing a historical synthesis means one is using the work of other scholars, synthetic work is extremely important and requires significant skills of reading, thinking, imagining, composing, and narrating. Which also means that synthetic work is as prone to be bad history as it is likely to be good history. It all depends upon the skills and the critical thinking caliber of the author/s.

What follows is a lightly updated version of an article I wrote as a 2nd-year PhD student, a time when I was still learning the basics of historical thinking and writing.]

[For a PDF version of this essay, click here.]

Background

In the 1770s, while America (the white settlers, that is) was preparing to break itself free of British domination, the eastern regions of India were gradually being incorporated into Britain’s international empire. Having extracted, from a captive Mughal emperor in 1765, the rights to collect revenue (the diwani) in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, the East India Company and the British Parliament were keen on setting up an efficient system of administration in the new territorial acquisitions. Warren Hastings, the Governor of Bengal, came up with a “Plan for the administration of justice” which was expected to streamline the allegedly fragmented and corrupt state of affairs in those provinces. This 1772 “Judicial Plan” set in motion discourses and events that would have a lasting effect on jurisprudence in India.

The 1776 publication A Code of Gentoo Laws; or, Ordinations of the Pundits: From a Persian Translation, Made from the Original, Written in the Shanscrit Language was a direct consequence of this plan. [The word ‘Gentoo’ is derived from the Portuguese word for Hindus, and was commonly employed by Europeans in the eighteenth century.] Apart from its limited use by East India Company administrators, A Code of Gentoo Laws, (hereafter “A Code”) was published in Europe too, and introduced Europeans to new knowledge about Hindu culture and philosophy. This article looks at the historical context of the production of this text, and describes how translation–from South Asian languages to European languages–was used as an instrument of power and legitimacy by the East India Company: to legitimize, for the colonized, the imposition of a foreign administration on them; and, for the colonizers, the preservation of the native customs and “laws” of Indians.

English law or “Indian law” for Indian territories?

Late eighteenth century British empire-building in South Asia was a process rife with uncertainties and novelties. Britain had no experience of administration in India, and Company officials constantly stressed the existence of already sophisticated (even if “superstitious”) cultures and traditions. The deep penetration of Mughal authority and imperial symbols, and the supposed “unchanging continuity” of ancient Hindu customs, ensured that India was not a blank slate for the British to begin imposing their own systems. In the debate over the adequacy of English law in the administration of Indian natives, the rhetoric around India’s ancient origins would ultimately gain the upper hand.

Company official Luke Scrafton, for example, dismissed observations of other Europeans that “there are no laws in this country; that the land is not hereditary; and that the emperor is universal heir.” While there were “no written institutes,” he informed the British that the Indians did “proceed in their courts of justice by established precedents.” As for the nature of what he called “old Gentoo laws”:

“The Bramins say, that Brumma, [Lord Brahma] their lawgiver, left them a book, called the Vidam, [the Vedic texts] which contains all his doctrines and institutions. Some say the original language in which it was wrote is lost, and that at present they only possess a comment thereon, called the Shahstah, [the Dharmashastras] which is wrote in the Sanscrit language, now a dead language, and known only to the Bramins who study it… and though all the Gentoos of the continent, from Lahore to Cape Comorin, agree in acknowledging the Vidam, yet they have greatly varied in the corruptions of it: and hence different images are worshipped in different parts… their [the Hindus’] customs are reckoned part of their religion, being sanctified by the supposed divine character of their legislator. If conjectures are permitted, I should suppose, that Brumma was king, as well as legislator.”

Such juxtaposition of religion with jurisprudence and legislation can be explained by what Cohn terms the “India as a theocracy” model which some Company officials subscribed to. As per this interpretation, the subcontinent was characterized by established and highly detailed codes of conduct that had the power of law and had already been worked out in the ancient era. Warren Hastings, of the 1772 Judicial Plan, believed that “even the most injudicious or most fanciful customs which ignorance or superstition may have introduced among [the Hindus], are perhaps preferable to any which could be substituted in their room. They are interwoven with their religion, and are therefore revered as of the highest authority.” He was convinced that the Hindus were content with their pre-existing religious “laws” and thus it would be far easier to simply employ those in the new administrative plan, especially since the natives “would consider the attempt to free them from the effects of such a power as a severe hardship.” [Clearly, the only “Hindus” that Hastings conversed with were elite, privileged-caste groups which had no reason to do away with the status quo.]

In many ways, Warren Hastings enabled the “birth of Anglo-Hindu law”. The translator-author of A Code, Nathaniel Halhed, profusely thanked Hastings for his sustained patronage and his “happy suggestions”. As per the “Judicial Plan”, Hastings wanted to establish a new administrative system on “the most equitable, solid, and permanent footing.” One of the ideas underlying the Plan was the belief that an important reason for the success of the subcontinent’s Mughal empire was the Mughals’ non-interference in the traditional ways of life of their Hindu subjects. Hastings also believed that the people of India “do not require our aid to furnish them with a rule for their conduct, or a standard for their property”; the inhabitants of India were not “in the savage state in which they have been unfairly represented.” He quotes in one of his letters about the belief among some elite in Britain that “written laws are totally unknown to the Hindoos... From whatever cause this notion has proceeded, nothing can be more foreign from truth. They have been in possession of laws, which have continued unchanged, from the remoteIt is these beliefs that enabled the insertion into the Judicial Plan of what is perhaps its most well-known phrase to this day:It is these beliefs that enabled the insertion into the Judicial Plan of what is perhaps its most well-known phrase to this day:st antiquity.” In his considered judgment as Governor, “it would be a wanton tyranny to require their [the Natives’] obedience to [laws] of which they are wholly ignorant.” Halhed shared this belief, writing that “much of the success” of the Romans arose from the fact that they had exercised toleration in the religious matters and beliefs of their subjects.

It is these beliefs that enabled the insertion into the Judicial Plan of what is perhaps its most well-known phrase to this day:

“.. in all suits regarding inheritance, marriage, caste and other religious usages or institutions the laws of the Koran with respect to Mahomedans, and those of the Shaster [Shastras] with respect to Gentoos, shall be invariably adhered to; on all such occasions the Moulavis or Brahmans shall respectively attend, to expound the law...”

[To see the above quote in its original context, see page 26 of this 1772 publication.]

The “original” and the translation

In March 1773, a few months after the Judicial Plan was conceived, the members of the principal court of justice in Calcutta wrote to the Company Court of Directors in London emphasizing the need for a “code of laws” for an efficient daily working of the British courts in India: “… in order to render more complete the Judicial Regulations, to preclude arbitrary and partial Judgments, and to guide the Decisions of the several Courts, a well digested Code of Laws, compiled agreeably to the Laws and Tenets of the Mahometans and Gentoos, and according to the established Customs and Usages, in cases of the Revenue, would prove of the greatest public Utility.” This arbitrary division of the natives of Bengal into two supposedly uniform groups of Mahomedans (Muslims) and Gentoos (Hindus) was carried over from Hastings’s 1772 plan, particularly the recommendation mentioned in the preceding paragraph.

The socio-culturally meaningless but administratively attractive classification of the people of Bengal (and by extension India) into just two major categories based on supposedly uniform and monolithic religious labels – Mahomedans and Gentoos, or Muslims and Hindus – was to persist in the governance logic of the colonizers throughout the colonial period, and would spill over in the political realm of native communities with disastrous consequences. To quote Elizabeth Lhost’s summary: “The 1772 plan receives criticism for erasing differences—regional, sectarian— within Hindu and Muslim communities. Not only did the plan single out two distinct communities—while ignoring others (e.g., Christians, Jains, Buddhists, Parsis, Jews, etc.)—but it also grouped all Muslims and all Hindus into seemingly uniform categories, ignoring diversity and difference within these communities… As a result, scholars have critiqued the plan for inaugurating a Company-led campaign not just to ascertain the laws of Hindus and Muslims but also to simplify and to unify the application of those laws across the subcontinent’s diverse populations.”

What the Company administrators wanted now, as evident from the letter mentioned above, was a “compilation of the Hindoo laws with the best authority that could be obtained.” The general belief among the British was that the Brahman pandits were the best authority on legal matters for the Hindus, and that the most authoritative texts were those of the Dharmashastra tradition. Hastings believed that the pandits in India received a “degree of personal respect amounting almost to idolatry, in return for the benefits which are supposed to be derived from their studies. The consequence of these professors has suffered little diminution from the introduction of the Mahomedan government, which has generally left their privileges untouched.” The colonial project of codification thus involved the employment of native Brahmans who would produce a compilation of “Hindu laws”, supposedly in the ancient, millennium-old tradition of the Dharmashastras, but for the express purpose of assisting modern British judges in modern British courts of law on Indian soil.

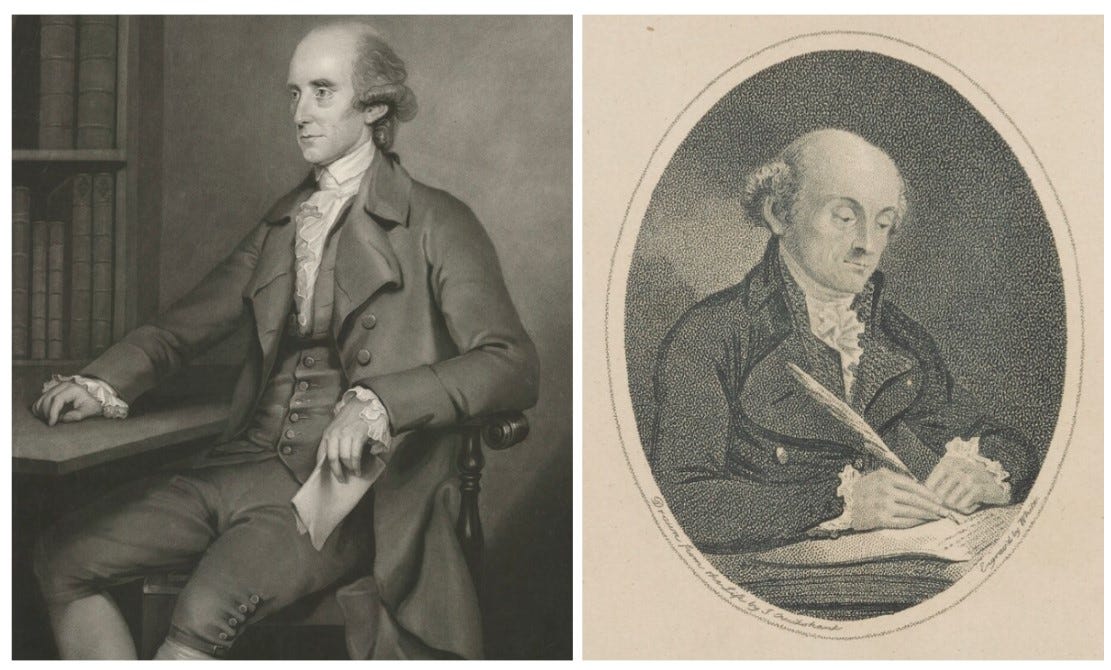

Hastings recruited eleven Brahmans from different regions of Bengal. They were all stationed in Calcutta, and began working in May 1773. Hastings considered them to be experienced and of high repute, and some of these pandits were among the most renowned in Bengal. Many were associated with the court of Raja Krsnacandra of Nadia, “the most brilliant center of classical learning in Bengal” then. The names of all eleven of them are listed in A Code, which also lists the names of the texts (“the most authentick books, both ancient and modern”) that the pandits used as references in this endeavor. The work was completed in under two years, by February 1775. The compiled Sanskrit work was called Vivadarnavasetu (“a causeway through the sea of litigations”).

The Vivadarnavasetu – the original Sanskrit work behind the English volume A Code of Gentoo Laws – featured a “preliminary discourse” in which the pandits described the events leading to the compilation endeavor. This section can be read as a justification for [elite-caste] Hindus requiring their separate laws under the British administration, and as a hagiographic account of the efforts of Hastings towards encouraging that idea. The pandits wrote that the ancient “Gentoo religion” was “ravaged by the armies of Mahomedanism” following which the state of affairs changed “so that in every Place the immediate Magistrate [Rocher says that the Sanskrit term for ‘king’ was translated as ‘magistrate’ here] decided all Causes according to his own Religion; and the Laws of Mahomed were the Standard of Judgment for the Hindoos. Hence Terror and Confusion found a Way to all the People, and Justice was not impartially administered.” This was of course a misleading account of Islamic law in Mughal India: for example, we have already seen that most Company officers, including Hastings and Halhed, testified to the preservation of Hindu laws and customs in the Mughal empire, with Hastings saying, as noted above, that the Mahomedan governments had left the privileges of Brahmans “untouched”.

The pandits further proceeded to describe how “a Thought suggested itself to the Governor General, the Honourable Warren Hastings” to work for an impartial administration of justice that gave proper attention to each religion and to the tenets of every sect. To this end it was decided to invite pandits and compile a book which, “delivered in the Hindoo language, was faithfully translated by the interpreters into the Persian idiom.” The Persian translation was already underway in December 1773 [note: Vivadarnavasetu was completed in Feb 1775], and was made via a Bengali oral rendering of the pandits’ Sanskrit. The translator has been named as Zain ud-Din ‘Ali Rasa ‘i by Rocher, but we do not know much else about him. She mentions William Jones [in his capacity as a judge at the Calcutta Supreme Court in the 1780s] saying in one of his letters that the translator was “a Muselman writer from the Bengal dialect, in which one of the Brahmans explained it to him.”

The process of translation that led to A Code of Gentoo Laws was thus considerably convoluted: Sanskrit to Bengali oral, Bengali oral to Persian, and then Persian to English. It is noteworthy that the first major British colonial effort to ostensibly reinstate ancient Hindu customs and laws which had supposedly been “ravaged” by Muslim invaders, actually involved substantial Muslim and Persian mediation. One must also note that the “original” Sanskrit version here (Vivadarnavasetu) was not some ancient, readily available text that was simply cleaned and refurbished by the eleven Brahmans, but was a newly created text for the specific use of the East India Company administration, based on the Brahmans’ knowledge, experience and on older texts available to them. Vivadarnavasetu, in other words, was a modern text for modern and colonial purposes, despite the veneer of its adherence to ancient and “native” traditions.

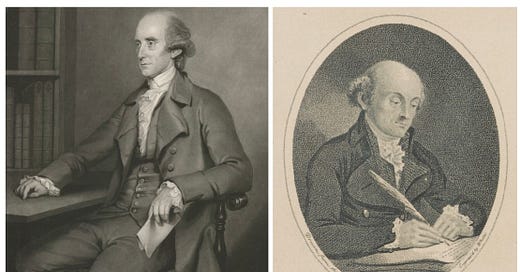

Nathaniel Brassey Halhed was personally chosen by Hastings to translate the Persian version into English. Halhed came from a wealthy family in London, and was educated at Harrow and Christ Church. He probably studied some Persian before leaving for Calcutta, where he arrived in August 1772 at age 21 to begin working as a “writer” and accountant, and then Persian translator, for the East India Company. Halhed’s arrival fortuitously coincided with the approval of the judicial plan and with the efforts to codify Hindu and Muslim “laws”. After Halhed’s A Code, an early codified version of Muslim law in English, titled An Epitome of Mohammedan Law, was published ten years later by Francis Gladwin.

Despite the efforts involved in its creation, and its first-of-its-kind nature, the legacy of A Code in jurisprudence in India was short-lived. Cannon contends that it never enjoyed authority, was sparsely executed, lacked references, and abounded in errors. The assessment of A Code by William Jones, who dominated British understanding of India, of Hinduism and of Sanskrit in the period after Hastings, was especially negative. It did not help that Jones was a judge at the Supreme Court in Calcutta. For him “a translation, in the third degree from the original, must be, as you will easily imagine, very erroneous." Jones was of the (obviously racially refracted) opinion that though Halhed had faithfully performed his part in producing the code, "the Persian interpreter had supplied him only with a loose injudicious epitome of the original Sanscrit." He also made the then pandit of the Supreme Court “read and correct a copy of Halhed's book in the original Sanscrit” while Jones’s own work on a new code proceeded. In a letter to Governor-General Cornwallis (who succeeded Hastings) in 1788 Jones asserted that “whatever be the merit of the original, the translation of it has no authority… Properly speaking, indeed, we cannot call it a translation.” Nevertheless, until the next code, A Digest of Hindu Law on Contracts and Successions, was published in 1797-98, Halhed’s code remained an important source for British judges.

Concluding remarks: Creation Through Translation

The creation of A Code was driven by the quest for legitimacy of the early East India Company, but the quests for accuracy and authenticity took a backseat in the process, and what ended up being created through the translation was much less and simultaneously much more than a comprehensive code of “Hindu law”.

As mentioned earlier, William Jones did not find the code reliable. He was also unhappy with the Sanskrit “original” which he thought was superficial in some aspects. What even Jones did not highlight, however, is that in pre-modern India, before the birth of Anglo-Indian law in 1772, “no uniform code of law was ever enforced anywhere across caste groupings, let alone everywhere in an imperial polity.” The principal legal actors or institutions were rulers, temples, and corporate groups (caste and sub-caste groups, traders, soldiers, agriculturalists, pastoralists, etc.). The practical administration of law occured primarily at the local, societal level. As Nandini Bhattacharyya-Panda writes, Sanskrit texts called “Dharmashastras” – which Hastings and the other officials considered as ancient law-books – provided prescriptive, normative or moralistic guidelines or codes of conduct for Hindus of higher castes, including Brahmins, and were not equivalent to the European version of legally enforceable rules. The shastric tradition was not static, and the guidelines were subject to flexibility and change. Besides, different regions in South Asia often differed in multiple ways in their legal traditions.

In other words, by fixing (in time) and then universalizing the Dharmashastric tradition from a single region (Bengal), the East India Company officials with their Brahman collaborators employed the ancient textual knowledge of India for unintended purposes and deviated from the tradition itself.

The inevitable processes of selection, translation, and interpretation, which went into the production of both the “original” Vivadarnavasetu and its translations, were bound to produce something new. The pandits even made some concessions to the purely administrative demands of Hastings, either incorporating material not ordinarily a part of the tradition, or modifying the emphasis on particular topics depending upon what the Company was more interested in. Bhattacharya-Panda claims that the pandits were not exactly collaborators with agency but were “paid informants trying to answer questions that they did not always understand.” She contends that the making of the code marked a passage from normative texts on correct conduct to clearly defined legal codes, and is thus an example of a colonial “invention” of tradition. She also argues that the Company officials appropriated the Dharmashastric tradition for their own administrative convenience. The Dharmashastras did not even contain a synonym for the term “law” as it was understood by British officials.

The two millennia-long tradition of revisions and commentaries came to an end after colonial intervention. Arbitrarily selected topics and passages from the old texts were used to define “Hindu law” - marking an “irreversible development” in India’s legal history. Additionally, the belief of Company officers in the possibility of constructing authoritative texts with which to govern, was based on profound misunderstandings of the dynamic, negotiated, and contested nature of Indian society and politics (and indeed society and politics across the world). The colonial administration’s patronage of Sanskrit legal treatises tended to privilege certain classical or scriptural versions over more diverse forms of royal and customary law existing in pre-colonial India. In late eighteenth century Bengal, the East India Company invaded and conquered not only a territory but a lifestyle and an epistemological space as well, creating new ways of living and thinking, new methods of seeking and addressing justice, and new forms of knowledge about India and Indians.

Colonial power was also created through the translation. The translation process – Sanskrit to Persian to English – embodied the traditional transfer of power as codes of law passed through the languages of the elites and the conquerors (Brahmans, Mughals and British). The collaboration with native elite scholars and the rhetoric of preserving native religions and customs, ensured that imposition of Company power in the late 1700s and early 1800s was met with minimum resistance both in Bengal and in Britain. Indeed, the translation projects of Hastings would later also assist the British empire in the production of colonial “subjects.” Indians being educated in English in the mid- and late nineteenth century, reading European translations of Indian texts prepared for a western audience, assimilated a whole range of Orientalist images. Importantly, they began preferring an access to their past via the translations and histories circulated through the colonial discourse.

By inaugurating a phase of representing India, its peoples and its civilization in the English language through translations, and stamping the (inadequate and often inaccurate) translations with colonial power and authority, Halhed and Hastings would unwittingly assist the vision of Thomas Macaulay half a century later, when Macaulay successfully proposed to the British Parliament the necessity of creating “a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern, - a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect.”